The City is Awake

The Way Home

Driving back on the long, straight causeway, he peered out through his windshield. Silhouetted by late evening sun, the city blurred at its edges, as if he couldn't quite catch focus. There was no surface to it, no clear figure to hold, leaving his vision to grasp aimlessly at its massive, amorphous form. As he approached, the sun was diffused then obscured, and he entered the city's long, trailing shadow. The face of it was punctuated by lights – an uncountable matrix of yellows and blues reaching far into the sky, surmounted at the upper edge by a bright strip of white marking the city's upper limit. Closer now, it filled his vision – the vast, chaotic face resolving into a near-endless field of built form: walls and windows, balconies and ledges in a colossal, open-weave mass of accumulated humanity. Playing across faceted surfaces in the darkening night, light spilled into clear air; as the city devoured him he glimpsed a solitary figure, staring out at the distant horizon.

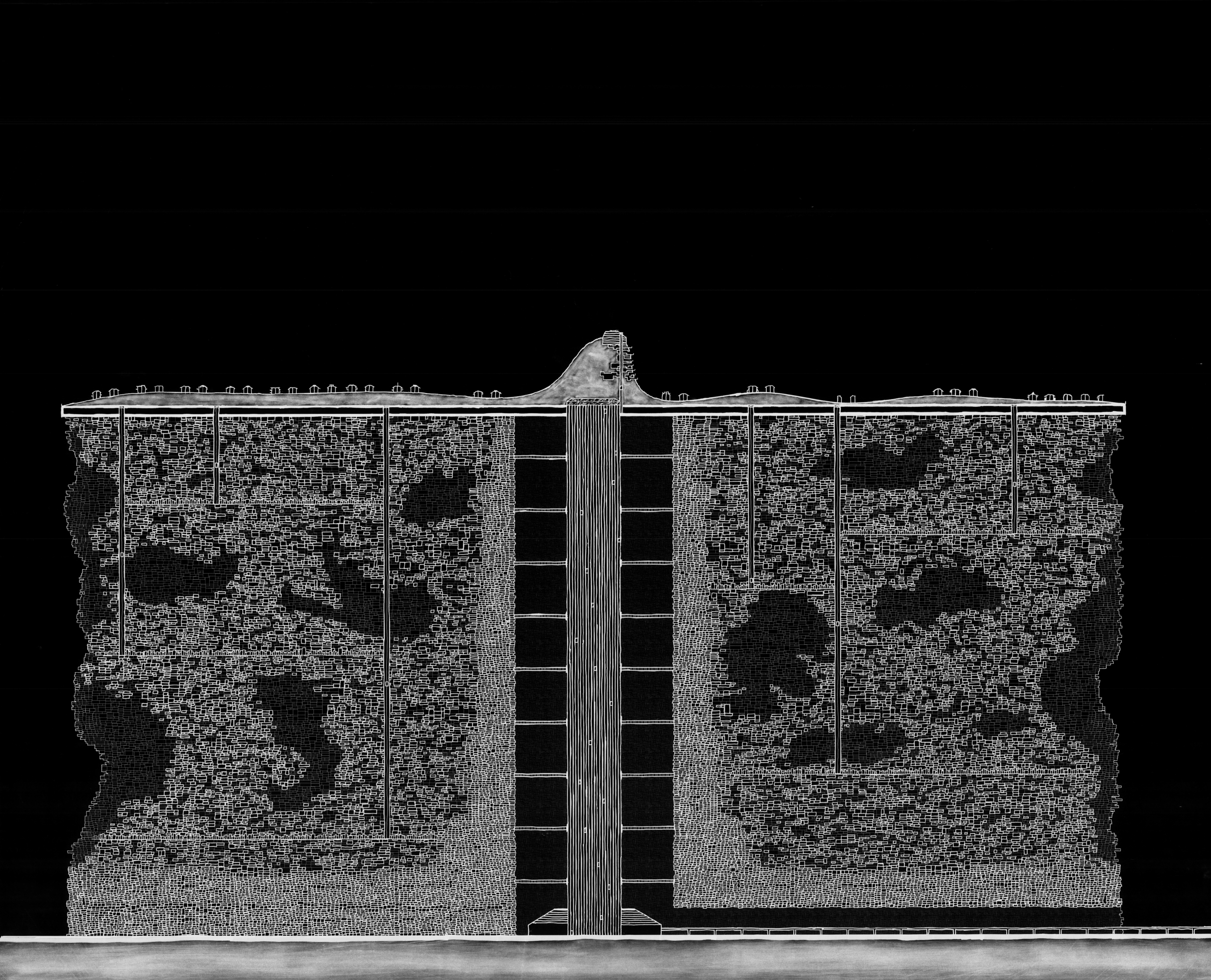

The road, its path undeviating, was quickly subsumed; like diving headlong into a pool of warm water, he was embraced and surrounded. this was the oldest part of the laissez-faire city, built before air rights and connection permits, built out to saturation; the city was a tunnel around the straight-run expressway as it burrowed inwards. A kilometre deep, buried in the centre of the complex, was the spine around which the whole organism was built – the Core. As a child, this view had captured him – indeed, it captured him still; standing at the base of the Core, he crooked his neck and looked straight up the length of this city's main conduit. It was a thousand metres from earth to roof, a bundled tube of elevators, pipes and columns a hundred metres across. Beams splayed out from the core at regular intervals, disappearing into four walls of solid urbanity which defined the shaft's edge. From here it appeared the city was supporting the Core, when in fact the opposite was true: the beams and columns, designed to support the official city above, were the armature around which the vernacular city had grown.

It had been a long day, but he had a way to travel just yet. Walking into the arrival checkpointthe line snaked out in front of him – due to unspecified 'credible intelligence', security was tighter than usual: shoes off, through the metal detector, through the explosives detector, file past the pattern recognition surveillance cameras, scan your travel documents then wait in line for an elevator. As he queued he saw a couple – probably Topsiders - breeze past on their way to the express elevators; it seemed security was more concerned with the contents of your wallet than that of your luggage. Reaching the front of the line, he paused a moment before filing in – he always liked to watch the city slide past through the elevator's glass doors. The rhythm of it was hypnotic – gliding silently past, three storeys every second, the solid wall of humanity blurred and melded into itself - two minutes from bottom to top, stopping only at its final destination, a kilometre above the ground.

Stepping off the elevator, he set out towards his ride back down. The Core, the city's busiest transit system, was in truth nothing more than a shuttle between the ground floor Arrival Centre and the Topside Transit Hub, one level below the roof. The Transit Hub sprawled across the width and breadth of the city, connecting the Core with a panoply of second-order elevators, tendrils stretching downward into the flesh of the sub-city. He lived on the Edges, about four hundred metres below roof level, but this circuitous route was his only way home. He took no particular pleasure from his visits to the Transit Hub - access to the roof proper was strictly limited to Topside residents and their guests, and was protected by yet another layer of security and surveillance. In that context, the portals in the ceiling of the Transit Hub seemed more mocking than salutary – the glimpse of open sky a cruel Topside joke on those heading glumly to their own burial. He had heard once that there were other ways to get around - extra-legal routes up through the Under-city that bypassed the Core and its surveillance-state nosiness – but he had never looked into it closely; he was happy to leave such pursuits to the refugees and smugglers.

Descending alone in his second-order elevator, he felt a low, distant crack shudder through steel and concrete. The elevator, disturbed by the sudden movement, began to slow; red emergency lights flickering briefly to life before the shaking subsided and his journey continued. Grown away from the earth's stable foundation, the city shifted and settled - tension and release propagating through its structure in semi-chaotic cycles. Every day, the passage of the sun caused temperature differentials from East to West; similarly, it was typically ten degrees cooler at the summit than it was on the ground. Like a colossal set of lungs or a beating heart, the city expanded and contracted by design, but recently, failures had grown in both frequency and severity. It rattled him to dwell too long on the subject – the city's mortality and his own, tied up far too close for comfort.

Stepping off the elevator, he was comforted by the familiar scene. This was a typical middle-ring, third-order street – lined with small shops and offices, it formed a convenient thoroughfare for locals on the route home. Above, the city stretched out indefinitely, layers of built form crossing and recrossing in the depth. A left turn took him past a dental clinic, a delivery office and his local grocers, bustling with distracted-looking homecomers. A short way on he came to a familiar, wide passageway and made his way down three flights of stairs to a sliding swipe-card door in black glass. Swiping through he emerged into an enclosed corridor, one wall glazed from floor to ceiling and opening out to the long horizon. This development, a new one, was at the absolute Western edge: the long, straight corridor, joined at either end to a fourth-order thoroughfare, extended the armature of the city, providing the skeleton around which its next layer would grow. He and his wife had purchased a Connection Right from the developer just on a year ago, and had recently moved into their new home; she was from the inner sectors, and was put off by the long drop below them, but he was captivated by the view.

Sometimes, in the early morning, he would sit out on their balcony. As the sun rose, he would watch the shadow of the city appear, cast long and low across the shallow waters stretching out to the West. His breath would catch in his throat, and he would be seized by a paralysing fear – a fear of the monster they had created, two and a half million lives inextricably tangled, waiting for the day the beast would turn on them.

Delivery

Her territory was one Cube – 100 metres long, wide and high, an imaginary volume extruded directly below her tiny office. Her stock in trade was movement – specifically, she owned and ran a delivery business, distributing small packages within a micro-jurisdiction in this city's heart. Twice daily a cart would arrive from the central distribution centre, dropping off and picking up packages. This was the arrangement: the parent company handled logistics and distribution down to third-order thoroughfares, while franchisees worked the 'last hundred metres', couriering the package to its final destination. It was, of course, a canny offloading of risk: first, second and third order delivery was large-scale, reliable work in this city. Down at the fifth, sixth, and seventh orders, passageways were narrow, addresses were inconsistent and maps were wrong if they existed at all. Instead, the company relied on its network of franchisees, hyper-local operations run by micro-entrepreneurs whose primary qualifications were fleet-footedness and an intimate knowledge of their neighbourhood; she possessed both attributes, and she didn't mind the work. The whole thing was a two person operation: her partner handled the office work while she ran. Hard.

She had run the numbers once, and now she knew them by heart: there were was something like twenty five hundred people living or working in her territory, in about a thousand buildings. Places around here averaged one delivery a week, which came out to just over fifty thousand drops a year. Working eleven hour days, six days a week meant she was on the job thirty three hundred hours a year, giving her 0.066 hours to make each delivery. This became her golden rule – four minutes per delivery. Four minutes to pick up a package, descend through the labyrinth, find the right door, make the drop and climb back up to street level, ready to do it all again. No-one else could do this job – no-one else knew the place like she did. Over the New Year, when the workload was heaviest, she would usually hire some neighbourhood kids for a week or two. They knew the place well, but it would still take two or three of them to make the one hundred seventy-odd drops she could do in a day.

At this point, it's all instinct and muscle memory: an address triggers an ideal route in her mind, and she takes off. Sector 3, 6-4-16-A? Out the side door, courier bag slung across her chest. Into the alley – down six steps and onto a gangway. Halfway along, hop the barrier onto a maintenance ladder, gloved hands sliding three storeys down to the roof of Mrs Fong's corner store. A quick leap off the roof and into another alley, then a sharp left at an unmarked door. Down three flights of stairs, then exit into an overlit corridor, past a classroom full of kindergartners singing nursery rhymes. Through the front entrance a left turn, careful not to lose her balance where the air conditioner still drips onto loose concrete pavers. At the end of the alley, squeeze through the narrow gap and she's there – ring the bell, drop the package and she's gone before they show up at the door. She has another delivery to make – another twisting, turning route to forge through this complex maze. On good days - on days like these - she and her city are one. She can't tell if her body was made for the city or the city was made for her – either way, the choreography is perfect: her mind, her movements and the space around her align, and she flows like a liquid through the veins and arteries of the behemoth.

Sunset

There used to be a garden here. Once, he had lain out until well past his curfew, on a turfed mound arrayed across the rooftops, and gazed at the darkening landscape. Back then, this was the edge – you could see sunsets, and rainstorms – birds would fly in and make nests under balconies and in the dark corners. There were no birds any more. You could sometimes catch a glimpse of the sky, shifting, vanishing and re-appearing as you walked, obscured behind neon signs, hiding and revealing itself as layers of the city parallaxed through view. The sunset was another question entirely – back here, deep inside the city, the day's direct light rarely made itself known. He knew a secret, though; as the seasons wax and wane, the sun travels its regular, predictable path – and every day, it shifts ever so slightly on the horizon. Encased deep within the city – separated from the outside by layer upon layer of aggregated humanity – this place had by chance retained a single, minuscule window on the Western horizon: on one day every year, for precisely 6 minutes, the setting sun would align with this fortuitous sliver, piercing the skin and burrowing deep within the city's heart.

He had found the place – or rather rediscovered it – by chance. Twenty years ago, when this was the city's leading edge, he understood this sector like it was an extension of his self; he could navigate the ledges, overhangs, balconies and maintenance ladders with the surety of one who knows nowhere else. As they both grew – the city and himself – they grew apart. He left home to follow the outward march of accretive urbanity, striving and scrambling to keep pace with its growth – to stay in contact with the edge and the outside world. When his father died, he returned home to a place he couldn't recognise: veiled now, hidden deep inside the beast, he found a different world – remembered fragments made foreign by their changed environment, a sense of enclosure either comforting or claustrophobic depending on his mood. At first he would get lost, mis-remembering a landmark or turning down a blind alley, but in his spare time he would walk and, slowly, reassemble a mental map of his home space. One day, walking with no particular place in mind, a moment of recognition stopped him in his tracks. To his left, in the fluorescent white of a vending machine's glow: a narrow alley spanned by a gentle arch grafting one anonymous apartment building to another; it was just wide enough that a child might reach out and touch both walls at once. Running his fingers along those same walls, cement render grey and flaked by time, he came through to a small, rear-facing right-of-way. For a moment, he paused – was this really the place? Light, spilling down from bathroom and kitchen windows, carried humid air and the ambient hum of extractor fans; green plastic trashcans in place of the climbing vines he remembered. Nothing was the same, but so much was familiar - the shape and size of the space, a doorway or a downpipe: forms and functions, drawn and redrawn but never erased, awaiting a knowing eye to re-connect present with past. At the far corner, two water heaters dripped and hissed onto stained concrete, threatening to scald him as he squeezed through the tiny space between. Beyond, fresher air and the slightest breath of wind told him what lay around the corner: opening out, a tiny, remnant rooftop littered with pipes and conduits - no longer the garden he remembered, but similar enough to kick him with a jolt of familiarity. The garden was gone, but the view was more spectacular than ever; the three dimensional city arrayed before him in all its complexity. And that single patch of sky. And that moment of almost incalculable good fortune, to stumble into this space on the very day the sun's last light dove into city and landed just here. At first he came back often, hoping to catch again that peculiar alignment of human and cosmic, but he soon determined that the phenomenon would repeat itself once and once only every year. The vast complexity of this system produced, for him, a single, simple rule: on August the sixth of every year, between 6:32 and 6:38 in the evening, he would be here. Every year, in the orange glow which illuminated this corner of the city for those few short minutes, he would stand in that fleeting patch of light and be returned to the city that he once knew.

This year, he was late. Down the alley, he dashed across the back passage and felt the sting of the water heater as he brushed past; around the corner, he burst out onto the rooftop at 6:33 to see nothing. He checked his watch; the time was right, but it wasn't there – the shaft of light, the thread that held his city together, his tenuous connection to the outside world and to the past – it wasn't there. Turning to face the view, his eyes to the horizon, he saw no gap in the middle distance. A pinprick of light seeped around the edges of a scaffold, faded fast, and was gone. In its stead, the city glowed.

At the Edge

It wasn't the drop that unsettled her most. Her husband thought it was the drop – a brand new apartment at the edge of the city, from their balcony it was a straight 600 metres to the ground. He had grown up on the edges so none of this fazed him, but he tried to be accommodating. But it wasn't the drop.

True, she had grown up deep inside the city – for the first six years of her life, she saw neither earth nor sky. That far in, scale is compressed; as a child she would roam under fluorescent strip lights for hours, only dimly aware of the hundred-odd metres between her and solid ground. When she began to look beyond her childhood home - her achievements carrying her out to the middle ring - it wasn't vertigo, but the opening-up of space which bothered her most; in particular, she was conflicted by the open voids which suffused much of the city. These empty volumes, unintentionally precipitated by arcane building regulations, laid the city open in all directions, expanding her perspective and sparking her curiosity. But still missed the city's deepest parts, their tactility and richness of connection, and she spent much of her college years cocooned in her dorm room, comforted by its intimacy and closeness.

She had yet to come to terms with living on the edge of the city. Part of it was social, of course – her husband, sceptical as he was of his home-sector's oblivious self-indulgence, had the benefit of long experience, and could negotiate the milieu with a deftness she had yet to acquire. Mostly, however, it was environmental, or rather physical. Once they had brokered the relevant structural, connection and air rights, when they first sat down with an architect, she had one non-negotiable – the apartment must face inwards as well as out. On the edges this was atypical – their neighbours all turned away from the city, orienting their dwellings and their lives to the outside world. The wide panorama, the sunset and the open air – this was the primary attraction of the Edges, and the typical Edge-dweller sought to take full advantage. By contrast, theirs was a home in two halves: a lower wing, dark and contemplative, addressed the city's layered inner space; above, a fully glazed open plan kitchen/lounge painted white, leading onto a balcony and, beyond, the long horizon. Once they moved in she spent most of her time downstairs; when things got particularly bad she would retreat further, to their walk-in closet, and read. There, sitting in an armchair dragged in from the bedroom, she could stretch out her arms and touch both walls at once. It wasn't the drop that unsettled her most - it was the horizon. The endless, flattening expanse of vision she saw every time she looked out that window – space, vast and undifferentiated; the world reduced to an image of itself. Turning away, she would trace her fingers gently along the smooth concrete wall and return downstairs.

Topside

It always comforted him to see it from the sky. Viewed from above, the city in its most perfect expression. From here, it was almost diagrammatic – four square kilometres of elegant urbanity lifted from the blighted, waterlogged soil and thrust into the air. Beneath it, sheltering under its protective wings, a vital, striving colony of men and women spurred on by example to heights otherwise unattainable. This was the city he loved, a beacon of self-determination in a broken landscape, like the phalanstery of old.

As the helicopter drew nearer, the features of the topside came into view. Coming in low and acute, he looked down at the far-off floodscape as it was momentarily replaced by the chaotic aggregation of the Under-city, in turn wiped from view by his familiar home. Past the infinity-edge river-way which surrounded the Upper City, the gentle roll of artificial terrain spread out before him. Neatly ordered row-houses arranged obligingly along oak-lined streets formed a patchwork of neighbourhoods, dotted here and there by squares and wooded parks. This idyllic townscape was set off by the Topside's defining feature: a rocky outcrop surging a hundred metres into the crisp, clear air, pierced by the apertures of apartments buried inside and culminating in austere, stony-faced solemnity with the city hall.

His helicopter made its final approach, touching down on the roof of city hall, and the mayor stepped out at the pinnacle of this complex, piled-high city. Pausing for a moment, his eyes absorbed the scope of what man had wrought. Laid out before him, this foursquare city of sixty thousand-odd citizens was a testament to the power of man's will – a wonder of technical achievement worth fighting to defend.

His day had been long, and his meetings tiring; taking leave of his aide, he headed for the elevator down into The Rock. The short trip took him directly to his front door within the buried apartment complex he called home. Unlike the topside's spread of terraced townhouses, whose designs were more or less uniformly tasteful and unadventurous, the apartments carved into The Rock were subtractive expressions of their owners' will, for better or for worse. On purchasing an allotted volume in the hillside, he had engaged an architect from the Under-city to craft his ideal space. Topside architects were accustomed to form-making in the open air - the best Undersiders, by contrast, honed their craft deep within the city, cheating volume and stealing light from wherever they could find it; their aesthetic genesis lay not in the moulding of form, but in a truly three-dimensional understanding of space and its manipulation.

Long ago, he too had come up from below. The blue skies called to him, and he was compelled to answer. As a child, he would ride to the Transit Hub and stay there for hours, staring up through the portals or out at the horizon until security would arrive to shepherd him away. This, the will to rise – the siren call of the sky - had been the animating principle of his life.

It was in danger, this city – it had always held within it the seeds of its own destruction. The forces of entropy tore at it from below, welling up through any crack, clambering to tear down that which had been built. Order is not a natural state – the world tends to chaos, and only a strong hand can hold it down.

Special Delivery

There was more than one way to get around in this city - in fact, there were many: the true three dimensional city was a utopia of free movement. Escape, from whatever you were running from, became trivially easy in this interlocking matrix of rich connections; spatial movement, so closely tied to social control, was impossible to regulate - the free city was, for all intents and purposes, ungovernable. This did not prevent them from trying - the Topsiders would exert ferocious control in those small areas they could: the Causeway, the Arrival Centre, the Core and the Transit Hub together formed a contiguous, tightly governed sequence of spaces linking the Upper City with the outside world – without the correct travel documents and identification, these sectors were strictly out of bounds.

This is where she came in. Officially, there was only one way for people or goods to move upwards in this city: through the Core to the Transit Hub, then down via second-order elevators. For those looking to elude the all-seeing eyes of the official city, she was the alternative. The first steps were more or less routine: somewhere between the causeway and the core, a person would disappear through a crack in the wall-like facade of the ground-level city - some time later, they would reappear at the door of her small, unmarked office in the inner sector. The fee subsequently negotiated and payable in advance would cover the passage of either an individual or their goods, with prices customised to the difficulty of the job - it was a hazardous endeavour, so passage wasn't cheap, but it was a damn sight cheaper than getting caught in the Transit Hub with a kilogram of contraband strapped to your chest.

First and foremost, she was in the knowledge business. Getting from the bottom of this city to the top wasn't intrinsically difficult – it was a long way up, but gravity provided the essential directions. The difficult part was reaching a specific place both efficiently and discreetly - this required knowledge and connections, and she was a keen collector of both. Once she knew the destination, she would devise a route and assign a courier: for common destinations – refugee quarters, certain disreputable import/export bazaars – the courier would know the way by heart; in the more difficult or far-flung sectors, she would consult her map.

Officially, there was no complete map of the city. The Topside was scrupulously recorded and the Edges were well documented, but the council had little interest in sending surveyors through the depths of the city – they would typically go out to the third-order thoroughfares, but no further. She, on the other hand, had a great deal of interest in mapping – spatial complexity may inhibit spatial control, but spatial freedom can come only from spatial knowledge. Hers was the best map in the city – knitted together over many years, it synthesised official directories, developers' surveys, delivery route maps and, first and foremost, local knowledge. Much of the data she had gathered herself – traversing the city time and time again, testing doorways, marking ladders, asking directions; the end result was her map – a three dimensional model of the city as it was, more complete an accounting of the space than any before. She kept it to herself, however – there were precisely two copies in existence. One, a highly encrypted emergency backup, was secreted deep within the city, its location known only to her - the other remained on her person at all times. A map is a powerful thing – spatial knowledge, spatial power, spatial control: if her competitors got their hands on it, she would be driven out of business. If the council got their hands on her map, it could change the very nature of the city.

Each of her couriers carried a small device, a hand-held holographic projector jury-rigged by a friend/debtor of hers. Before an assignment she would map out a route, load it onto a memory card and transfer it to one of the machines. In themselves, the devices were purely dumb – hard-coded to hold no more than a single set of directions. Occasionally, either by bad fortune or bad intent one would go missing, but they could never provide more than a tiny fragment of the master map, which never left her possession. Once activated, the projector would display an interactive pathway, the most direct route from A to B, and her couriers had learned to follow these directions religiously. The map was the most dangerous piece of data in this city's history, but remained for the time being a tool of business, a competitive advantage in a moneymaking game. Its true power – the latent potential to redirect this city's history – remained, for the time being, dormant.

She had been Topside only a half-dozen times. It was the most difficult job one could take, and she wouldn't trust it to anyone else. The first few times were frantic, breathless incursions into hostile territory, but on subsequent trips she had occasionally found time to observe and reflect on the official city. It didn't particularly appeal. She could see the attraction of the sky, the trees and the open space, but it was a bounded domain; all of the edges were hard, and there was nowhere to go but down.

This is the nature of the city – the boundary which excludes also encircles. Every act of segregation, every narrowing of the gate also tightens the noose, drawing the end ever closer. The city is alive. The city is awake. You think that you created it but it, in turn, created you – and one day soon it will throw you from its back and lumber on alone.

An abridged version of The City is Awake was first published in Fairy Tales: When Architecture Tells a Story, by Blank Space Publishing (2014).