Emporium Melbourne and the Central Retail Precinct:

The Effects of Quasi-Public Space

Suppose you are standing on the North side of Lonsdale Street in Central Melbourne. A little-used staircase - an old entrance to what was once known as Museum station - will take you under the street and out of the public realm. You are now inside the CBD's largest quasi-public space, an assemblage of shopping centres and department stores stretching more than 400 metres South to Bourke Street Mall. At the centre of this swathe stands Emporium Melbourne: a shopping centre, but more than that also. Opened in April 2014, Emporium is connective urban tissue: with 15 points of public access across 6 levels above and below ground, it stitches a sequence of stand-alone spaces into a continuous retail precinct of more than 180,000 square metres. In this act of connection, Emporium has brought about a new typology for Melbourne's inner city – a large realm of highly accessible privately owned space which is connected to but distinct from the public realm of the streets it weaves under, over and around. Through spatial and discourse analysis combined with small-scale quantitative data-gathering, this essay will consider the impact of this quasi-public space, both on its users and, more broadly, on the surrounding urban fabric.

In what ways are privately owned spaces different from public, if both permit public access? To answer this, we need to disaggregate the various rights users have in these spaces. Under the mantle of 'ownership', Kevin Lynch identifies five rights: rights of presence, use and action, appropriation, modification, and disposition. In Australia, private ownership conveys, in principle, all five of Lynch's rights to the owner. By contrast, on land that is publicly owned, members of the public have a presumptive right of presence, use and action. In the case of the shopping centre, the difference has important consequences – because a visitor has no legally enshrined right to presence, the centre's management can arbitrarily create rules intended to insulate shoppers from disruptive or undesired experience. Every shopping centre has just such a set of rules – in the Emporium, they are engraved in brushed aluminium plates mounted at the public/private threshold (figure 1). In some ways, the specifics of these rules are irrelevant – legal precedent suggests that shopping centre owners can invoke essentially any reason for excluding a person from their property. The specific prohibitions displayed in figure 1 should be read, then, as representative of the operator's most pressing concerns. Most of the items listed show a desire to maintain an orderly, unchallenging and homogeneous shopping environment (that is, a desire to flatten the sometimes confronting differences which the public street compels us to encounter). The final item, however, stands out: the meaninglessly general prohibition against 'inappropriate behaviour' is a declaration of impunity – a statement that the centre operator can and will control this space in any way it sees fit.

Figure 1: List of Rules, Emporium Melbourne

What is missing in the quasi-public Emporium that exists in the public streets around it? Disjuncture, difference, and the mostly benign conflict-and-resolution process which occurs when no entity has absolute control over a space. For pedestrians, this stems from the right to presence on the public street, a right which doesn't exist in the shopping centre. These differences between the shopping centre and the shopping street are long-established in the literature, but with every new shopping centre comes a new and unique set of rules and regulations. Dovey points out that the mall, like any regulated space, is vulnerable to rhizomic acts of resistance and appropriation; Emporium is no exception, but its mix of general and specific rulemaking points to a management willing to robustly enforce the terms of its control over the centre.

How is Emporium different to the typical mall? Embedded in the CBD rather than surrounded by suburban carparks, Emporium is designed to entice pedestrians away from the street. In this respect, it is like its department store neighbours; unlike a department store, however, a shopping centre relies on internal circulation for its success. Where space restrictions preclude the use of a traditional 2 level mall-and-arcade typology, the only option is to build upwards - figure 2 illustrates the spatial complexity of the resulting design by architects The Buchan Group. Figure 3 further abstracts this space, illustrating the basic circulatory structure of Emporium: a set of vertically stacked circuits connected by escalators at the South, North and North-East and tied back to its neighbours at various levels. Figure 4, a spatial syntax diagram, is modelled on Dovey's application of Hillier and Hanson's analytical method. The diagram shows connections between internal spaces and their relative depth from the street; in Emporium, we see a small number of connections to the public realm explode into a richly interconnected, 'ringy' quasi-public interior up to seven layers deep. Negotiating this depth is Emporium's foremost spatial challenge.

Figure 2: Exploded Axonometric View

Figure 3: Circulation Diagram

Figure 2: Spatial Depth Diagram, Emporium Melbourne

In conversation, Emporium project architect Ashley Sheppard emphasised the importance of attracting shoppers away from the ground plane and into the ringy interior of the mall. A key tactic here is the careful positioning and layout of escalators. At both Little Bourke Street entrances, Buchan Group has employed a split up/down escalator system, which allows shoppers to proceed directly to the Lower Ground or Level 1 (figure 5). According to Sheppard, the intention of this escalator layout was to divert shoppers away from the ground floor, “making sure that once people got into the entries, they had a clear, direct access to get straight up”. These two sets of one-way escalators appear to be serving their purpose, diverting between 40 and 50 percent of visitors immediately away from the Ground floor. The net effect is that the 'deeper' parts of Emporium are easier to get into than get out of. These one-directional links bolster the basic logic of the shopping centre – that the ultimate aim of the space is to draw patrons out of the public realm and into more controlled quasi-public space.

Figure 5: Split Escalator System, Emporium Melbourne

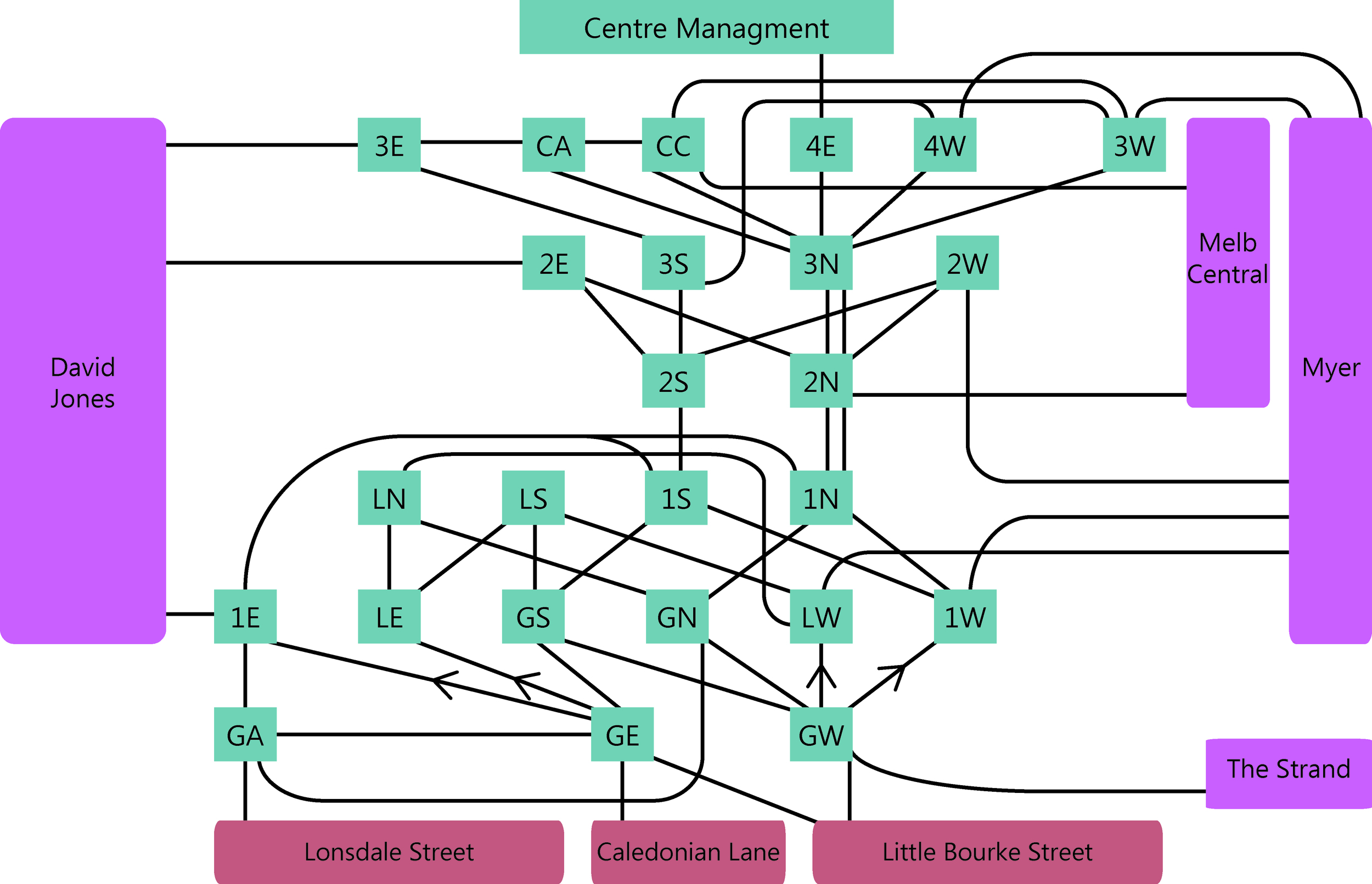

An analysis of Emporium cannot be limited to its site boundaries - we must consider its connections to the large quasi-public assemblage of which it is a central part. In conversation with Sheppard and Emporium centre manager Steve Edgerton, it was clear that the centre has been envisioned and designed as a connecting element within an as-yet unnamed assemblage we might call the Central Retail Precinct. This strategy, by which separately owned and operated retail properties are conjoined into a multi-block shopping precinct, is new to Australia but not uncommon in parts of Asia. In his analysis of these precincts in Tokyo, Kiwa Matsushita uses the term 'coopetition'. In a coopetitive environment, the scale of competition is re-framed, with neighbours working together to draw customers from more distant shopping hubs. It seems that the retailers of Melbourne's CBD have come to the same conclusion as their Japanese counterparts: while a conventional view would see Melbourne Central and Emporium as adjacent competitors, centre manager Steve Edgerton sees the two shopping centres, along with the Strand Mall, David Jones, Myer and the adjacent H&M store as 180,000 square metres of contiguous shopping space exceeded in size only by Chadstone, Australia's largest shopping centre. In that it seeks to compete with suburban super-regional shopping centres, the Central Retail Precinct might be seen as the next step in the revitalisation of Melbourne's CBD – the 1 million visitors Emporium reportedly saw during its first month of operation14 represents a significant influx of activity to the central city.

To understand the role of Emporium in this coopetitive precinct, we must consider the connections it makes to its neighbours. Of the centre's 15 entrances, 9 are skybridges: to Melbourne Central Shopping Centre in the North, and to the David Jones and Myer department stores in the South (Figure 6). This network of elevated walkways creates a large quasi-public realm entirely separate from the street. On a typical Sunday afternoon, these walkways see over 3,400 transits per hour, all of which occur directly from one quasi-public space to another without entering the public realm. This is in stark contrast to pedestrian behaviour at ground level. Here, both Myer and David Jones' Little Bourke Street entrances align with an entrance to Emporium. Despite this, the sliver of public space that separates the quasi-public realms dramatically alters patterns of foot traffic – for both stores, only 41 percent of those leaving the department store crossed the road and entered Emporium. For retailers and centre managers, the benefit of the skybridge is obvious – the task of diverting shoppers out of the public realm is diffused across the whole precinct, with shoppers subsequently injected into the heart of their centre. For shoppers, too, skybridges have an obvious appeal: a more convenient, unified shopping experience, in which they can flow effortlessly from one space of consumption to another. Having expanded beyond the limits of the city block through coopetition, the various owners and developers are building what Trevor Boddy has termed the analogous city. Melbourne does not yet have an analogous city of the scale and impact that Boddy described in 1992 - Minneapolis' skyway system, for example, puts Melbourne's four-block assemblage into context. Despite this, Melbourne’s nascent analogous city has many of the hallmarks of its larger counterparts. By leaping over the complex streets and sidewalks which otherwise limit the scale of quasi-public space, the analogous city increases urban stratification. Perching gingerly above the ground, it interacts with the street primarily by siphoning off shoppers into its pleasant, carefully controlled simulacrum of urbanity.

Figure 6: Skybridges, Emporium Melbourne

What can we say, then, about the overall impact of this newly formed quasi-public assemblage? First and foremost, we must acknowledge that it is simply too early to tell – it takes time for a new space to become part of people's routine and settle into the urban fabric. Looking forward, we can see some different but not mutually exclusive possibilities. Perhaps the relationship between the Central Retail Precinct and the rest of the CBD is not parasitic but symbiotic, a positive feedback loop whereby the vitality of the city enables ever-larger agglomerations of retail space and in turn the Precinct draws shoppers away from suburban malls, bringing more people to the city's streets. Walking down Little Bourke street on a weekend afternoon, it is possible to reach this conclusion. Even if the majority of shoppers are floating back and forth in glassed-in skybridges, there are more people, more vitality and more excitement here, on the street, than there was a year ago. Against this, however, we must consider the homogenising effects of quasi-public space. Will Emporium's customers, spilling out from this highly regulated realm, demand that we clean up our streets? Will they complain about the middle-aged man in drag with a marionette puppet, whose off-key singing harmlessly assails passers-by on the corner of Swanston and Little Lonsdale Streets? Will the kitchen hands ducking out the back of Chinese restaurants onto Caledonian Lane have to find somewhere else to sit and smoke? Is homogenisation a price we are willing to pay in exchange for a thousand shops under one roof? Perhaps, perhaps not – in Melbourne, as elsewhere, the balance between public and quasi-public is not yet settled.